PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CAREERS IN MUSICAL IMPROVISATION: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY OF THE MENTAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING OF PROFESSIONAL JAZZ AND IMPROVISING MUSICIANS IN NEW YORK CITY

Anjou, B. (2021). Psychological consequences of careers in musical improvisation: A mixed-methods study of the mental health and wellbeing of professional jazz and improvising musicians in New York City. The University of Sheffield.

Keywords: jazz, improvisation, professional jazz musicians, professional musicians, non-classical musicians, wellbeing, mental health, pandemic, Covid-19, PERMA, purpose, social isolation, burnout, flow state, resilience, fulfillment, MPA

ABSTRACT

This research aimed to ascertain the general well-being and psychological health of jazz and improvising (non-classical) musicians living in NYC, as well as the impact of Covid-19 on their mental health. This work also considers the effects of extended isolation in quarantine upon group jazz and improvisation - e.g. music that requires in person social engagement. A mixed-methods study was designed and conducted from June to September 2021, analyzed and reported in the fall of 2021. The methodology contained both an online survey taken by 110 participants self-identifying as professional jazz musicians based in New York City, and six qualitative interviews of professionals who lived and worked in NYC ranging between 11-43 years. Wellbeing and fulfillment of musicians were examined using the PERMA positive psychology measurement index. Psychological factors examined included making a living from one’s passion, psychology of social experience required of career musicians, financial losses, cancelled work, and how the pandemic affected creativity, as well as individual and social experiences of the phenomena of improvisation before and after quarantine. Results yielded high levels of depression and anxiety in participants mediated by an unprecedented period of quarantine rest and a lack of intrinsic purpose or motivation to practice caused by the 2020 pandemic. Implications of this research can further the understanding of mental health of professional improvising musicians, and improving mental health and working conditions for gig economy music workers in a post-pandemic music industry in the US.

BACKGROUND

My 2021 study aimed to build on a 2016 study by Help Musicians UK that documented high rates of depression, anxiety, and panic attacks in professional musicians at 70% in the United Kingdom, nearly five times the rates suffered by the UK general population (Gross and Musgraves, 2016). No such studies have been recently conducted nor published on musicians in the US.

Music requires intense training over many years that involves a plethora of visual, mental, aural, proprioceptive, and psychological challenges. Many people do not have the attention span or bandwidth to attain musical skills and frequently give up, citing a lack of ‘talent’. Yet, music is a skill that takes years of honing, mental focus, devotion, and discipline. Research shows that musicians have the highest job satisfaction, yet the highest rates of mental health issues due to the instability of the industry and a devaluation of their labor as valuable.

RESEARCH QUESTION: HOW ARE MUSICIANS GENERALLY DOING? HOW IS THEIR QUALITY OF LIFE, MENTAL HEALTH, AND WELLBEING?

Why do professional musicians suffer the highest mental health issues? According to my study and others, people who enjoy music (audience, listeners, non-musicians) have 1/8th of the mental health issues as the musicians creating it. Many people benefit from the labors of recording musicians - individuals, companies, organizations, arts presenters, music therapy patients, patients of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, hysterical paralysis, autism, and many other diagnoses. Research provides great evidence that music gives phenomenal aid to our physical, emotional, and psychological wellbeing on a daily basis. It follows there is a need for research to examine the mental health and wellbeing of this vulnerable and marginalized population.

AIMS: FILLING LARGE GAPS IN DATA

A literature review showed virtually zero studies on the mental health and wellbeing of musicians in the US, let alone living jazz musicians. A limited number of studies have mostly been conducted on classical musicians and published in Europe and Australia (Ascenso et. al., 2017). One study notably indicated higher instances of anxiety and depression in professional musicians than in semi-professionals and non-musicians. To fill gaps in research, I designed a mixed-methods study of mental health and wellbeing of musicians, especially focusing on jazz and improvising (pop, rock, etc.) musicians - to fill gaps both in quantitative and qualitative data, and to expand upon key research already conducted.

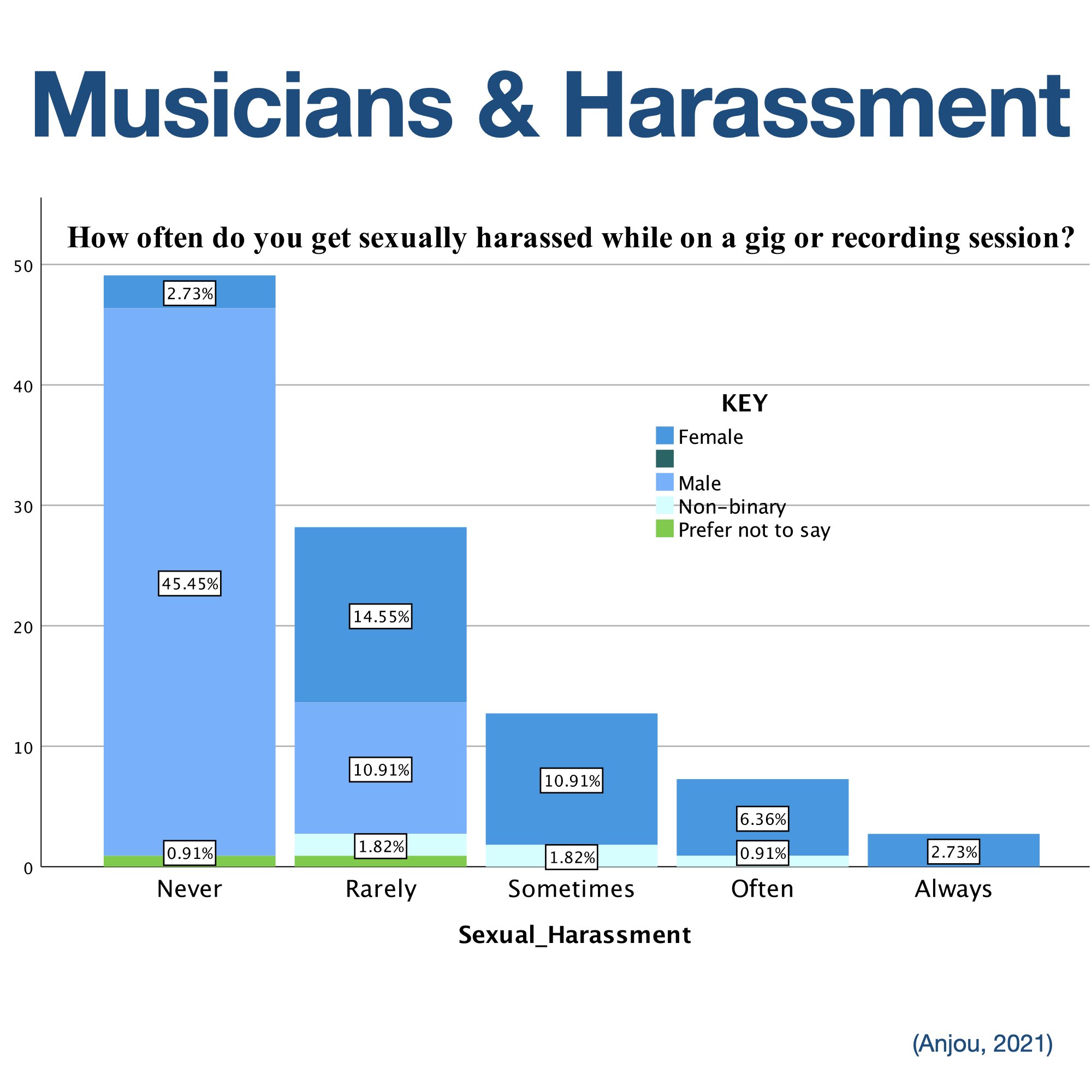

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH: SIX INTERVIEWS OF PROFESSIONAL MUSICIANS

Six professional musicians were interviewed at length (1-2 hours duration) remotely via zoom, regarding various topics. Subjects included mental health issues, lifestyle, challenges, teaching, virtual teaching, pandemic experience, covid-related income and tour cancellations, pandemic-related changes to their livelihood and personal life, living circumstances, social media, live performing, fulfillment, isolation / quarantine, and covid-adaptation. Major themes arised in terms of feeling separate as a ‘class’ from non-musicians, a large identity with a culture of suffering, identity as performer / musician, and unstable wellbeing based on daily perceived success and peer approval. Participants of both genders suffered from work-related trauma, harassment, underpayment, and struggles with showing paperwork to qualify for basic needs such as housing, taxes, unemployment, and artist visas.

QuantitativE RESEARCH: 44 qUESTION SURVEY, 111 PARTICIPANTS

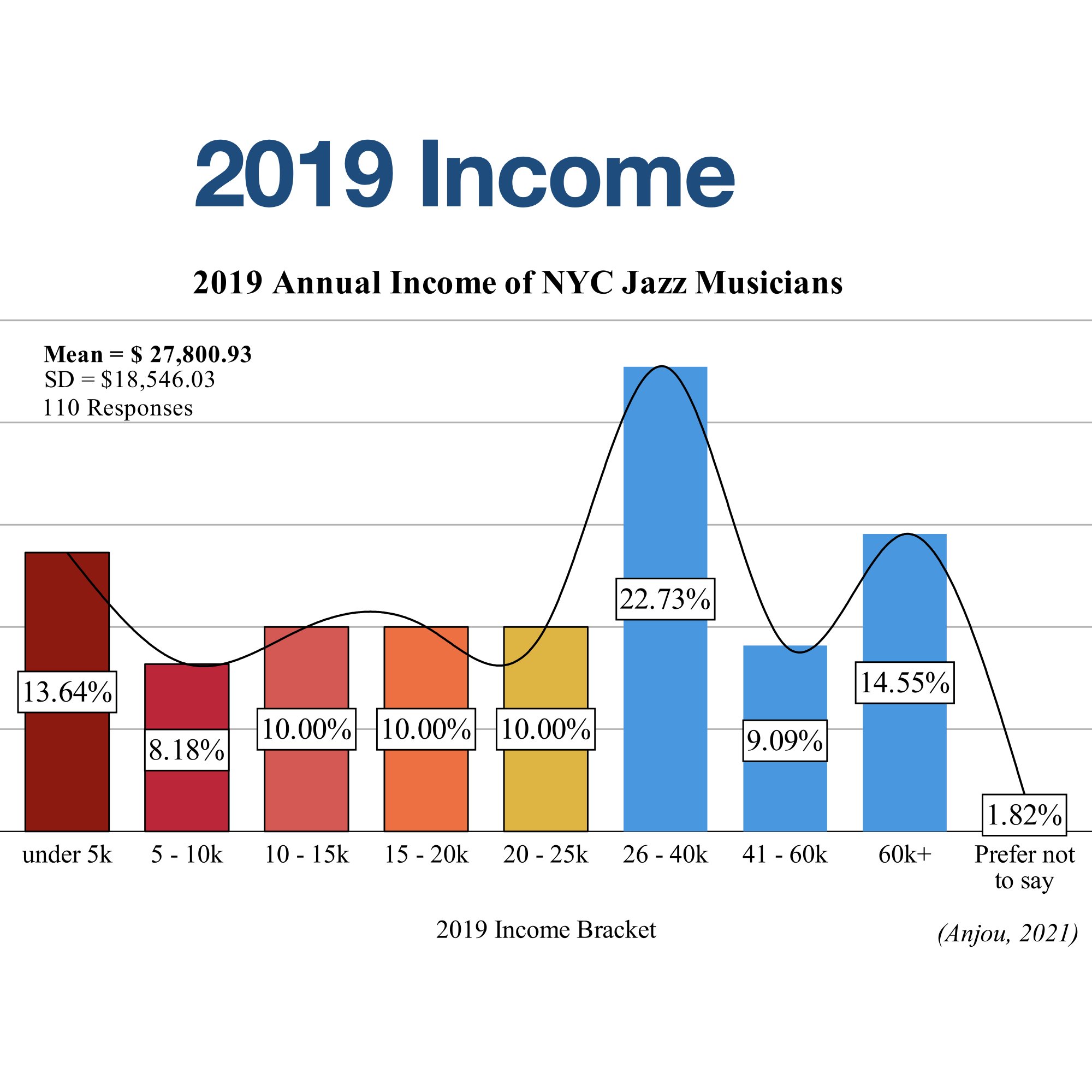

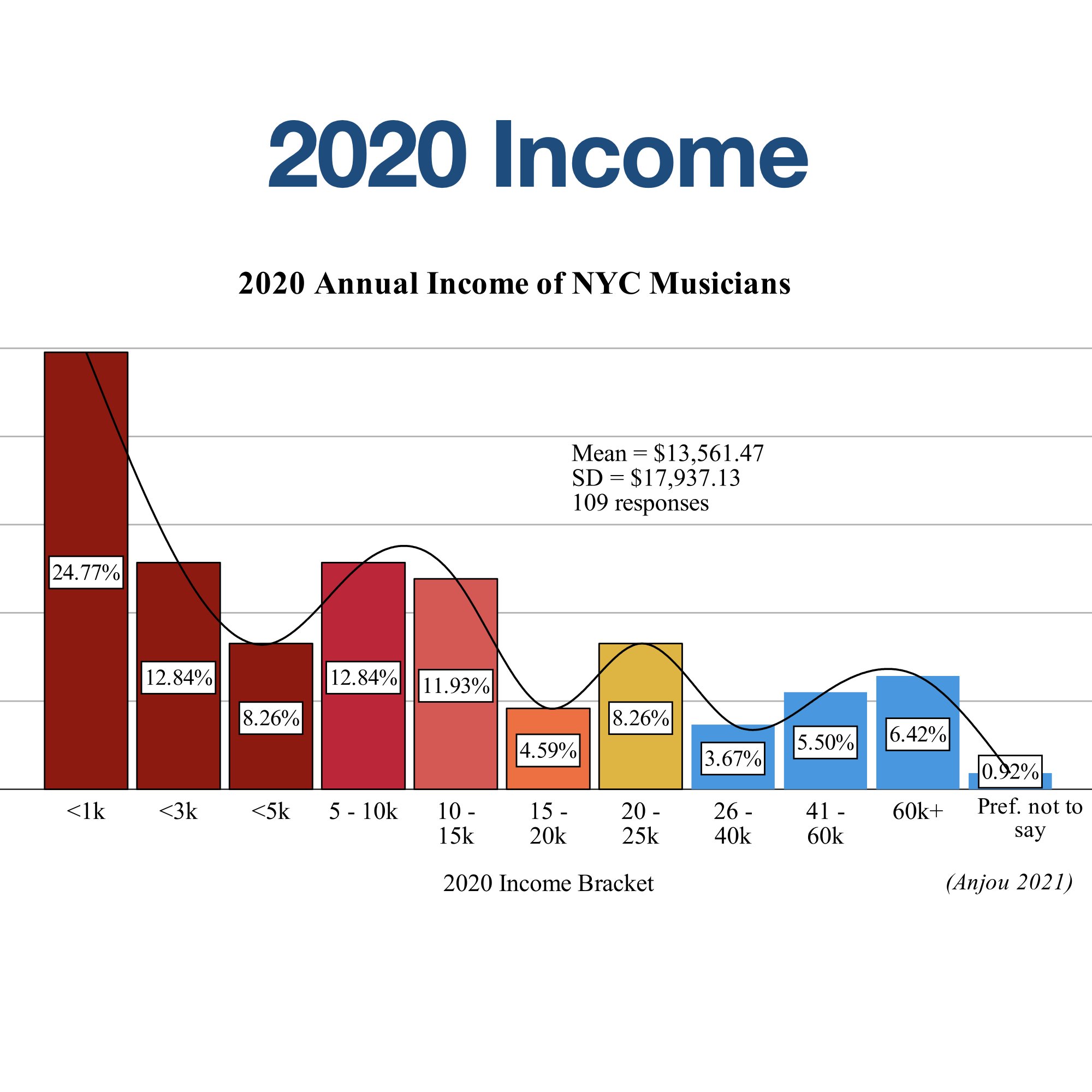

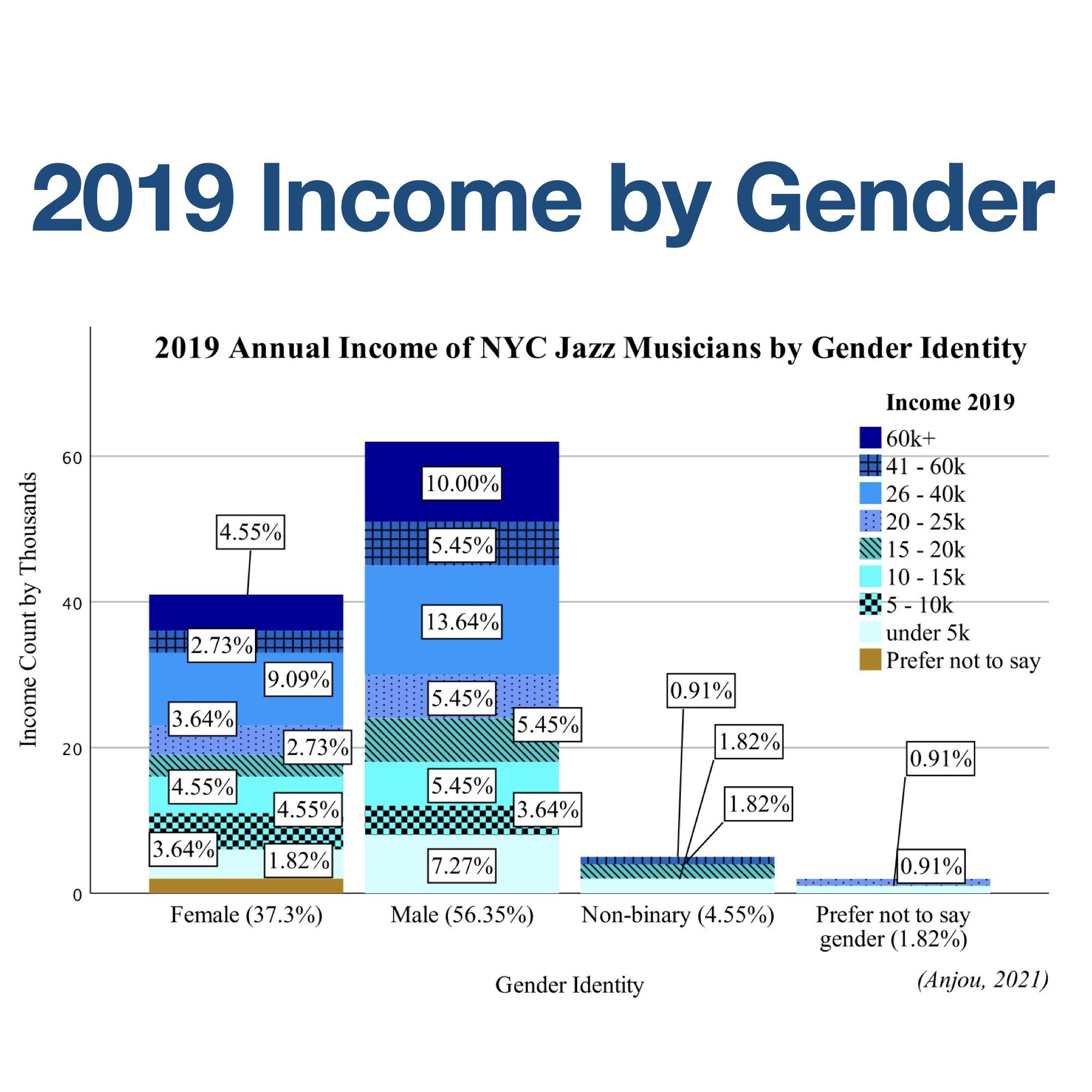

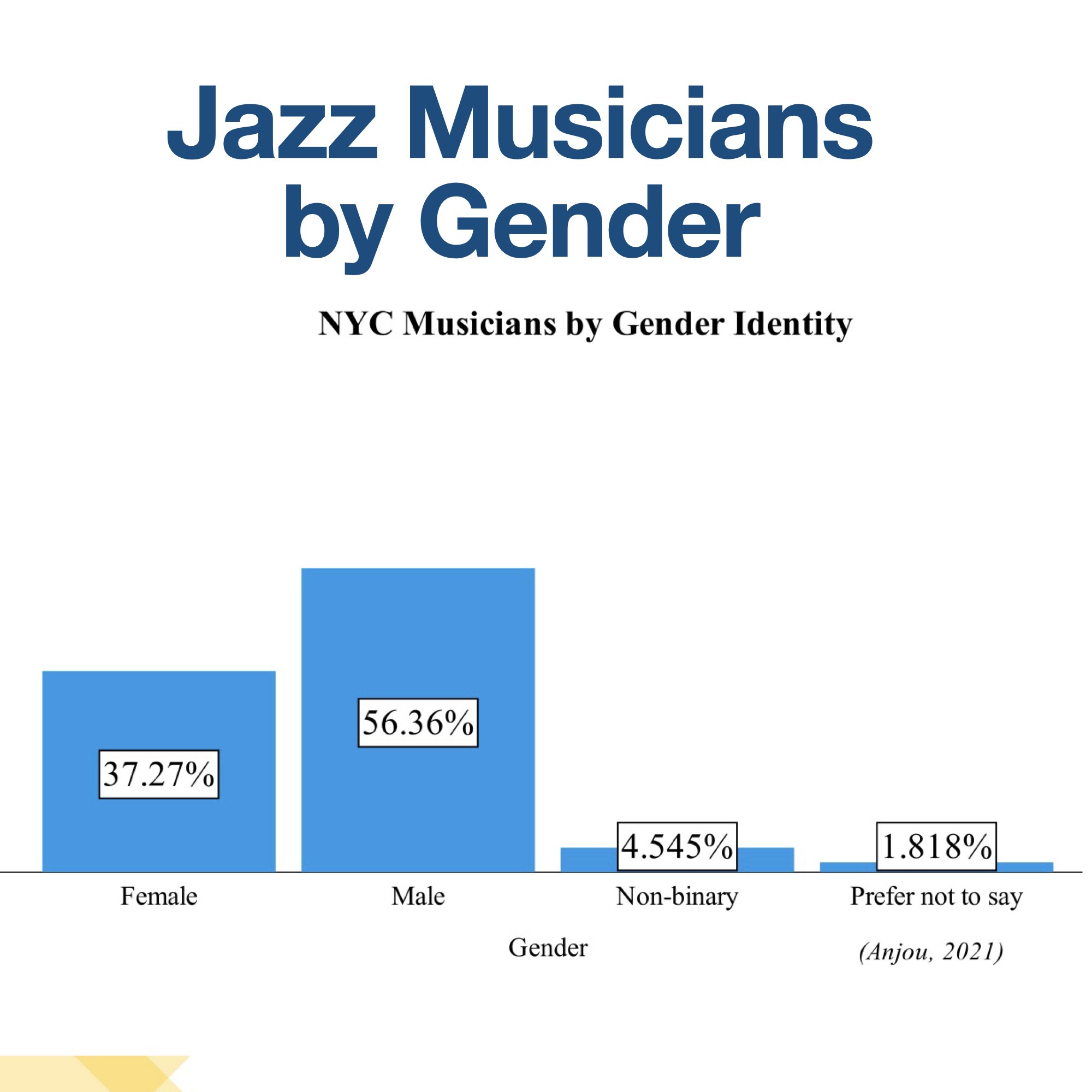

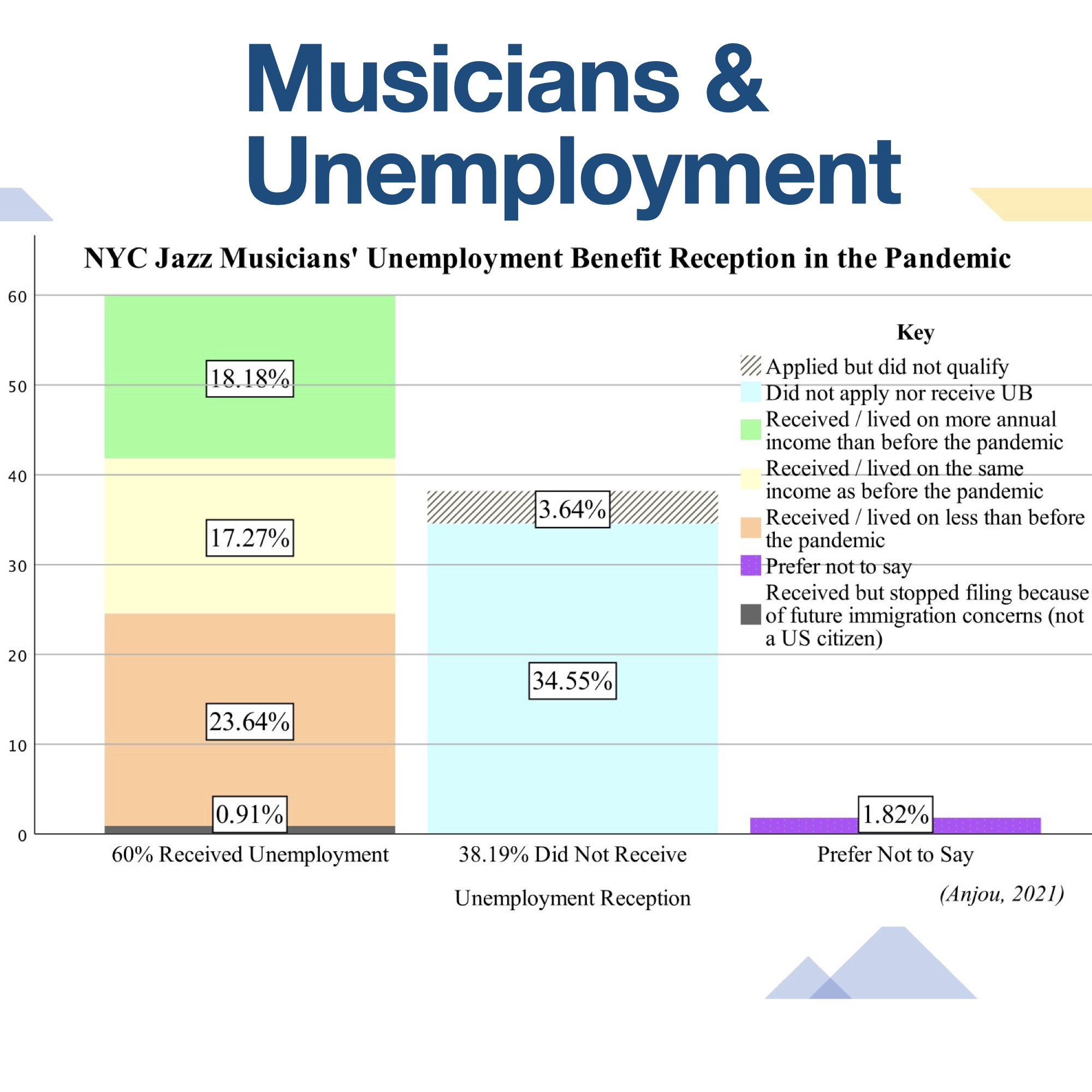

In my survey (approved by the University of Sheffield, presented at ICMPC-ESCOM 2021 and SEMPRE conferences), 111 full-time professional NYC jazz and improvising musicians (M=56%, F= 36%, NB=5%, Mean age = 45.6 years, 72% White - see graphs A and B) reported an average 2019 income of $27,800 (SD +/- $18k) before the pandemic. In 2020, over 45.87% of professional musicians earned less than 5k from music income in 2020 (Graph i and ii); 25% earned less than 1k, 58.71% earning under 10k, and 70.64% earned under 15k, showing an estimated 64.68% earned under the federal poverty line for a single household earner ($12,880/year, Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). Only 60% received unemployment benefits during the pandemic, and 38.18% did not receive unemployment, of which 35% did not apply and the remaining did not qualify, perhaps suggesting a population so used to disenfranchisement a majority don’t see themselves as qualified to be supported by the system.

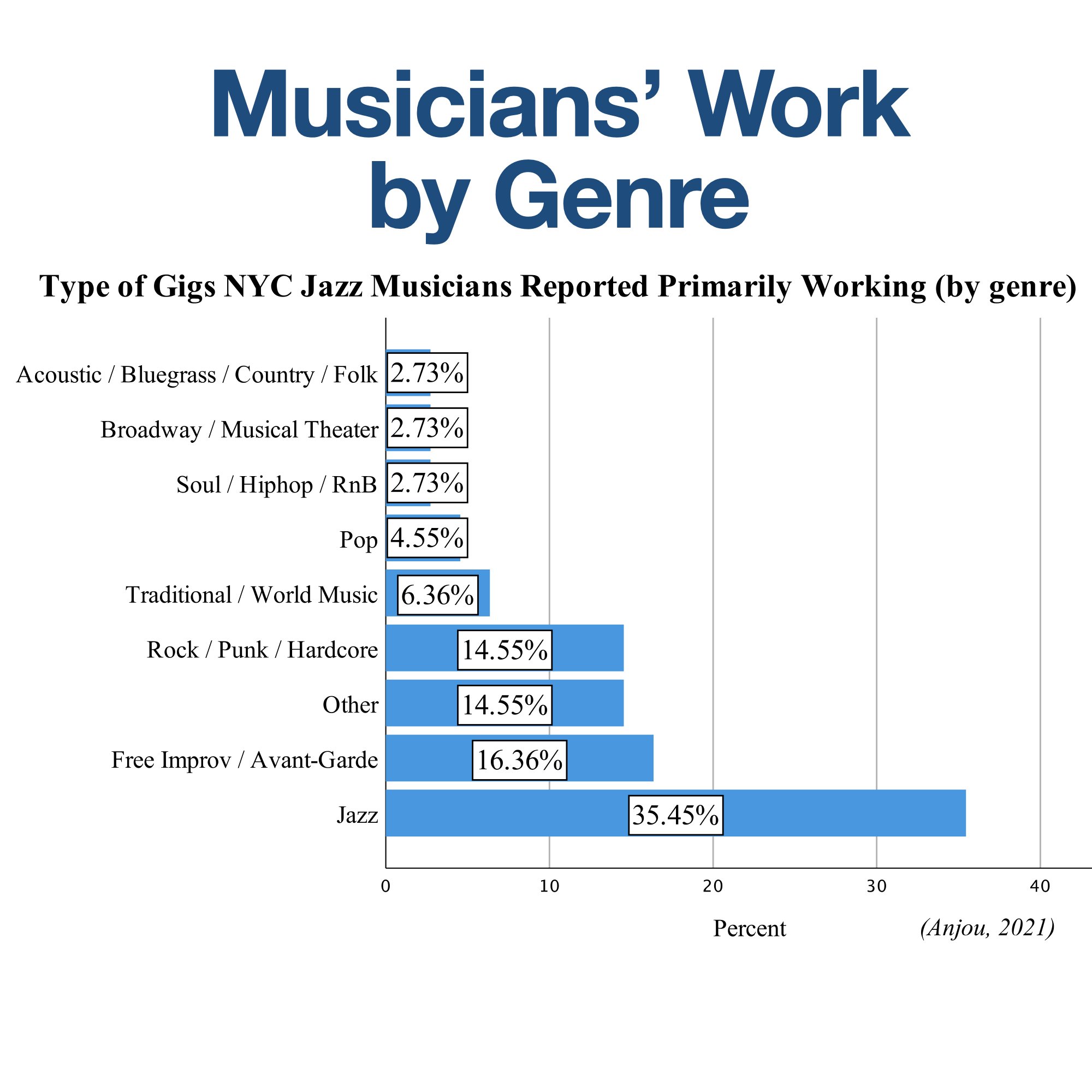

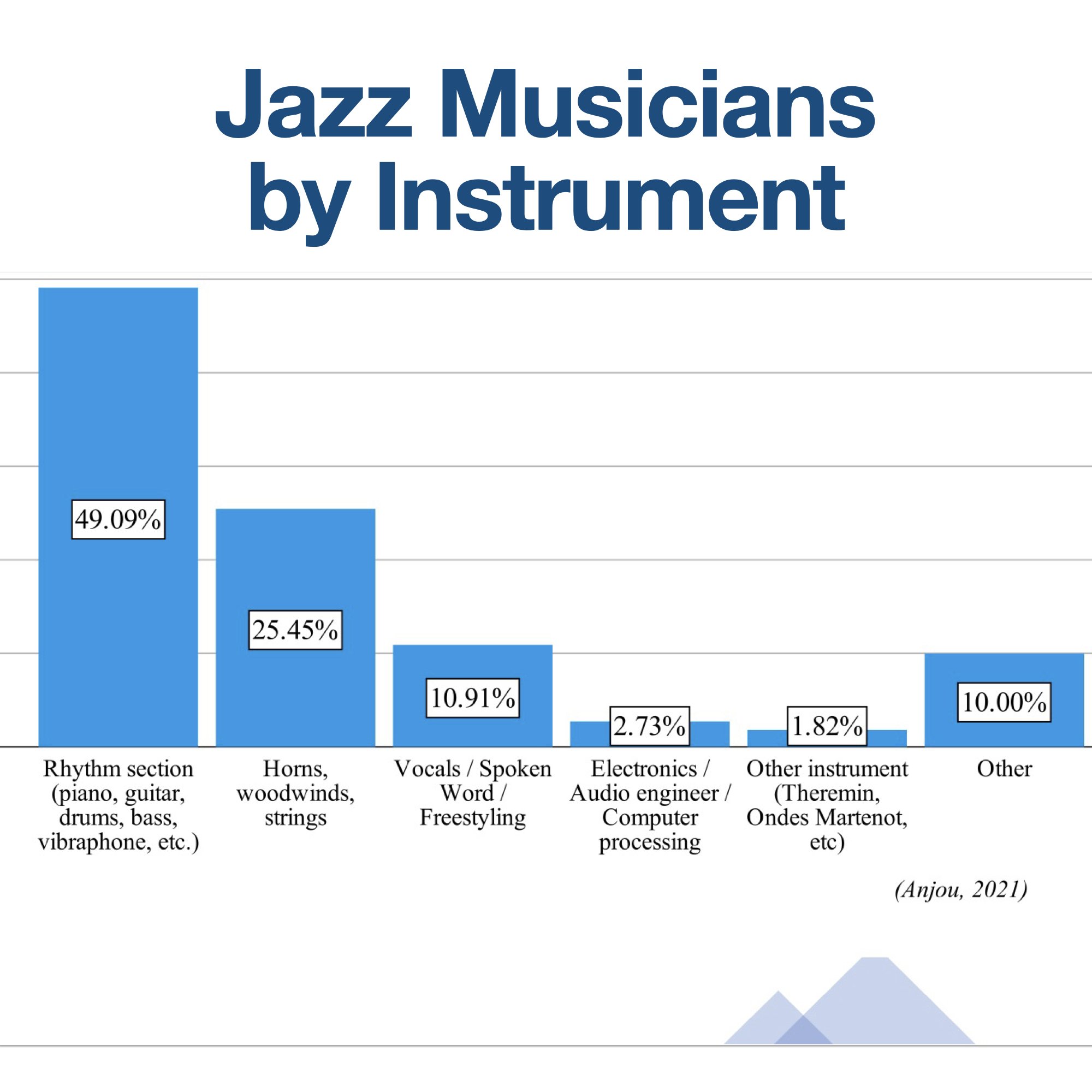

Less than 1% (0.91%) of the musicians indicated their primary livable income came from royalties and residuals from recordings. A majority 60.91% of musicians reported freelance touring and recording and teaching as their primary source of income, compared to only 4.55% reported Broadway or Union contracts as their primary source of income, and 28.18% who reported side day jobs or contracted teaching jobs as primary sources of income despite working full-time doubling as a performer (Graph 4 attached). A reported 41.82% identified primarily working as side musicians, and 39.09% working primarily as bandleaders (Graph 3). Instrumental key roles reported 49% rhythm players, 25.5% horn or string players, and 10% vocalists (Graph 2). Participants reported primarily working in jazz or improvisation (35.45%), free improv or avant-garde (16.36%), with pop, world, traditional, punk, country, broadway and other genres (Graph 1). While 86.37% have released original music, only 30% reported having released over ten combined albums and singles (Graph 5).

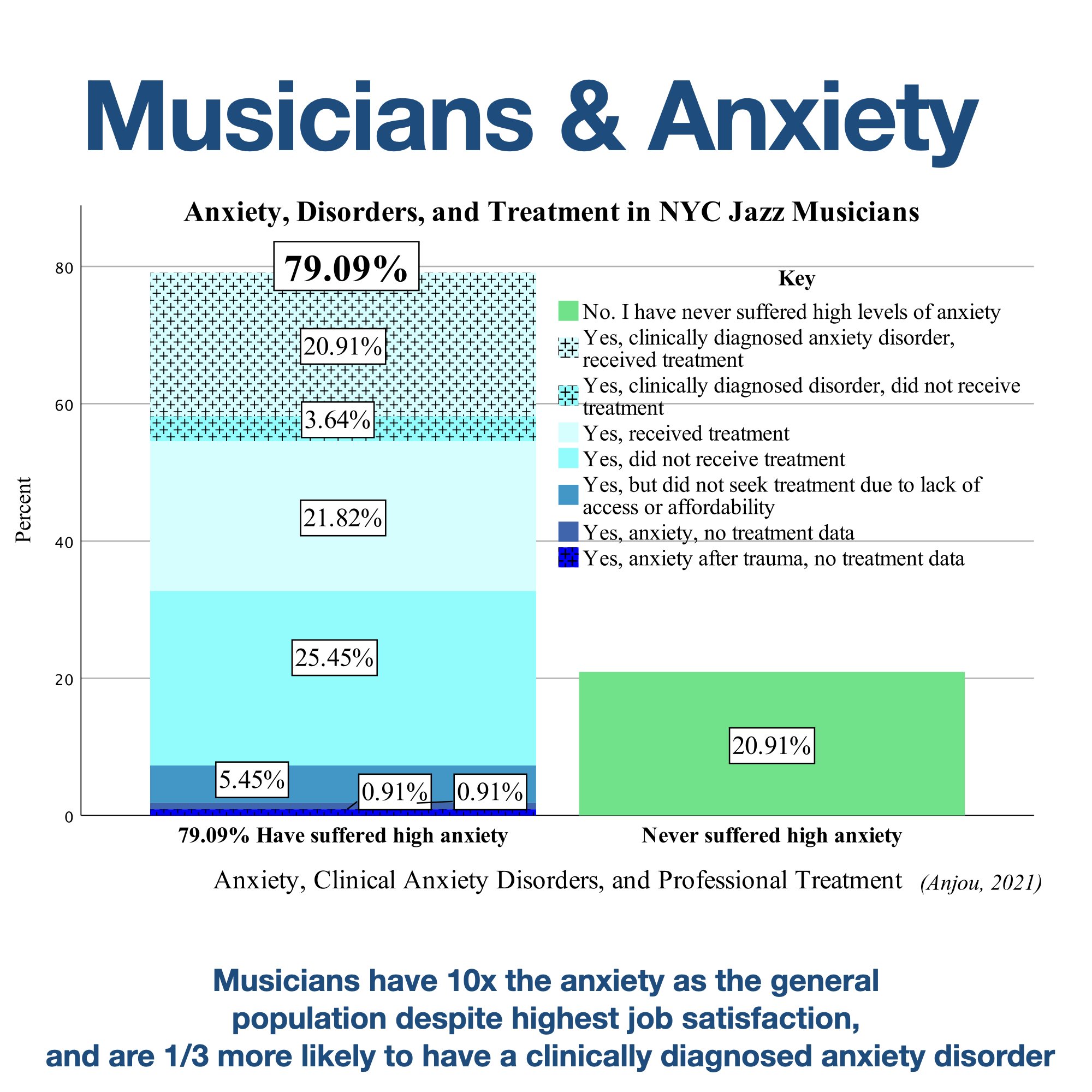

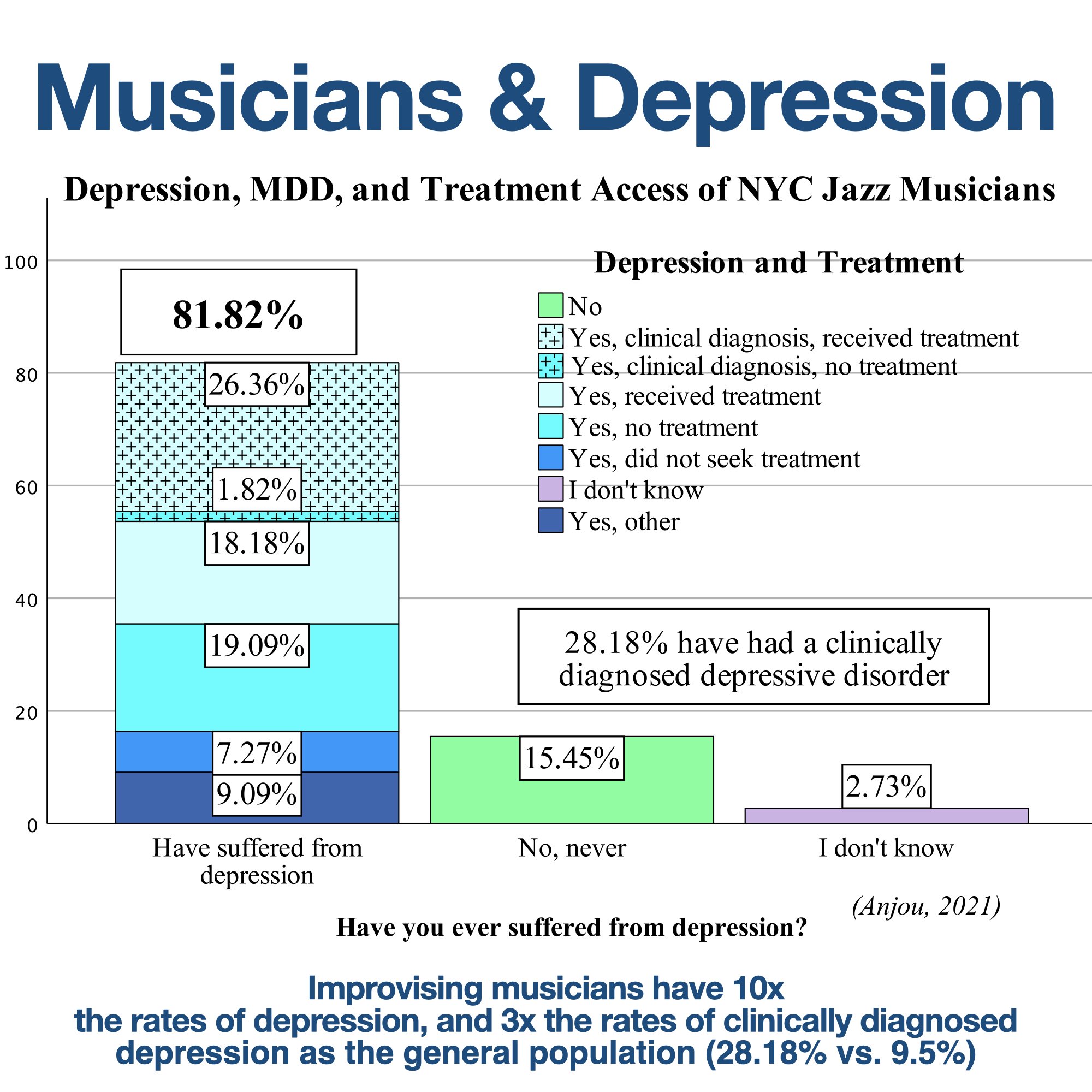

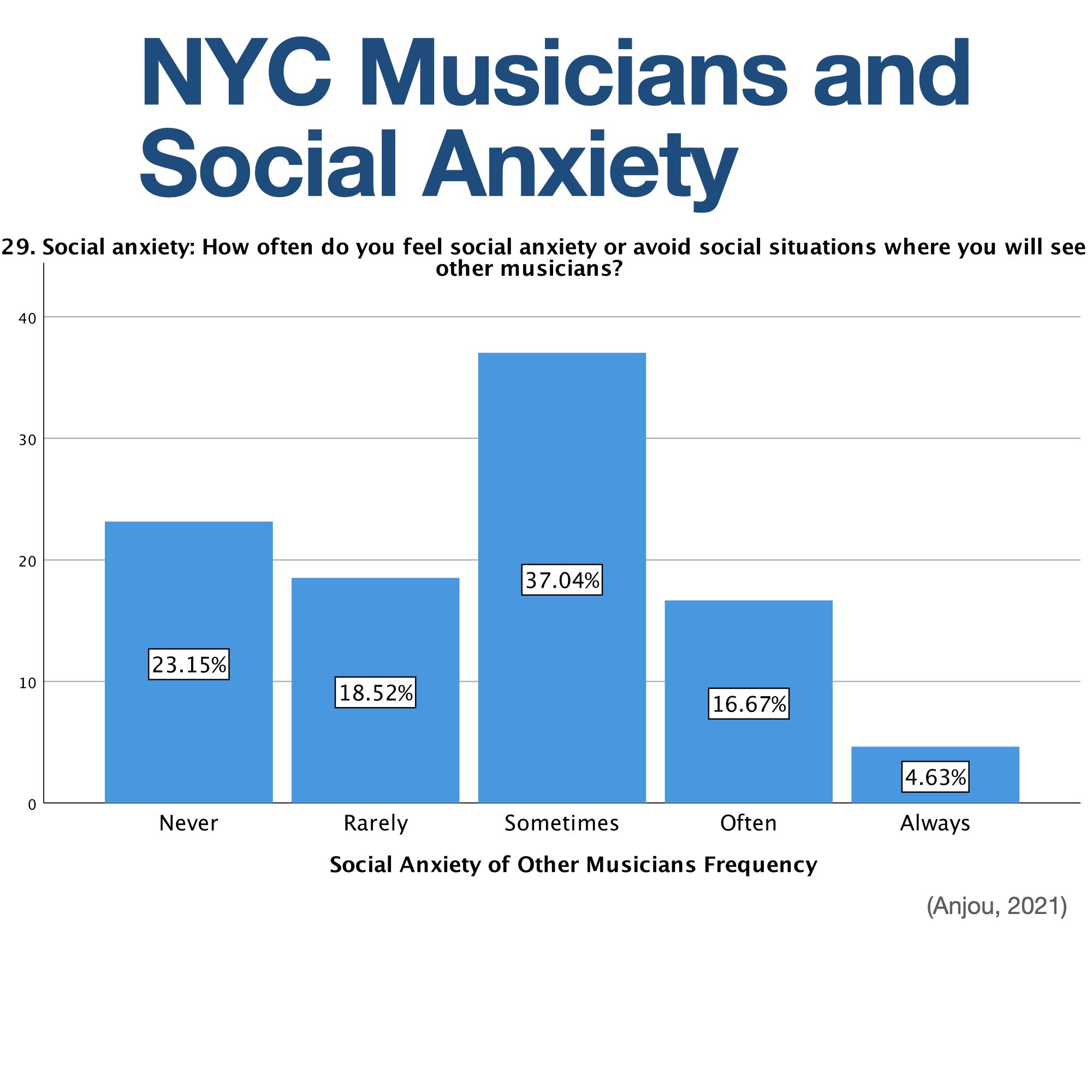

Jazz musicians reported suffering immensely high rates of anxiety and depression; 79.19% suffered from high anxiety (8x the rate of New Yorkers, 81.18% suffered from depression (10x the rate of the general population of New York pre-pandemic). This is significantly higher than 71.1% of musicians who reported suffering high anxiety in the UK. Between June to September 2021, 79.09% of surveyed NYC jazz musicians reported suffering high levels of anxiety, nearly ten times the reported rate of mental health disorders suffered by New Yorkers pre-pandemic, reportedly at 8%, according to the NYC Office of the Mayor (Thrive NYC, retrieved October 2021). In December 2020, 42.4% of adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression (Statista, 2021). Though the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2021) defines anxiety as a reaction to stress, “stress” levels from Covid-19 were reportedly increased for 67% of US adults, where 78% reported the Covid-19 crisis to be a major source of stress (APA, 2020). (Reports of stress levels in New York pre-pandemic were found to be somewhat higher than the rest of the US according to one 2011 report by the American Psychological Association.)

Regarding diagnosed mental health disorders, 24.55% of jazz musicians reported having had a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder at one point in time or another (see Graph 20A and 20B), compared to 18.1% of US citizens with a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder reported before the pandemic (ADAA, retrieved 2021), and similarly, pre-pandemic, about one in five (20%) adult New Yorkers reported having had a mental health disorder. We can infer that 1 in 4 jazz musicians have a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder, and are 1/3 more likely to have a clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder than non-musicians.

DISCUSSION: MIXED-METHODS SYNTHESIS

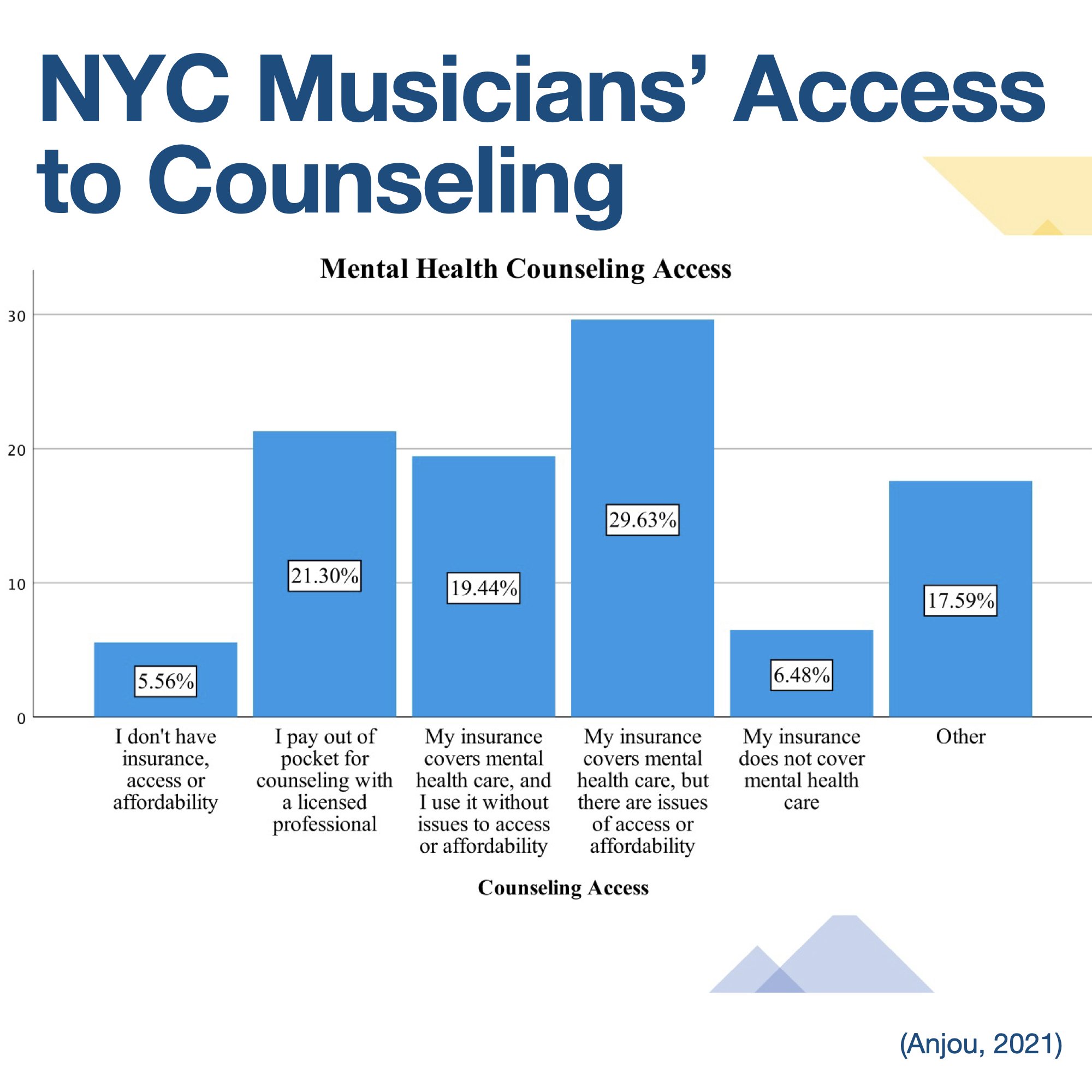

I compared the survey results to the qualitative data to analyze the situations of six professional musicians. The survey documented long-needed data on the low-income, career instability, and high mental health rates of musicians in New York. Qualitative data included in-depth details of career and personal instability (housing, income, social media, social exhaustion), as well as some mental health issues. Interviewees were apt to talk about what they needed most that they did not have or had to fight to access: support from the union / government, support from fellow musicians, and access to mental health and wellbeing care such as affordable gym memberships or counseling (consistent with the survey, only 19% had affordable access to mental health care without barriers). Survey results backed up qualitative data suggesting struggle, showing poverty-line income across the board in 2019 (27k annual income) and 2020 (13k annual income), 60% unemployment benefit reception,

Participants were also interviewed about their experience of isolation and the gap in playing music during covid quarantine since March 2020, or ‘covid playing gap” (CPG). The CPG ranged from 2 to 16 months, with one participant abstaining from a return to performing since March 2020 by August 2021. Musicians with a lower CPG indicated seizing outdoor playing opportunities during quarantine to continue to play safely with others and for communities in parks, porches, and streets. Some were able to transition into new notoriety from frequent outdoor playing. Musicians with a higher CPG tended to indicate more overall experience, ranged higher in age, and cited a general feeling of burnout and dejection from limited paid opportunities and a ceiling from ‘the same 1%’ of jazz musicians who repeatedly get all the funding, opportunities, and recognition, and exhibited a reluctance to return to performing due not just to covid exposure risks, but lack of pay and value. So in a way, a perception of value of ‘doing music’ was altered in some, but not all, participants. Regarding returning to playing, topics such as practicing solo during quarantine to keep in shape, and an initial rustiness upon a return to group gigs was experienced, but quickly dissipated with frequent repetition of group play and activity. Some felt “frozen”, while others did not. Most indicated joy upon a return to safe outdoor group improvisation, noting that casual jam sessions with friends and community to be more rewarding than the stress of gigs.

Finally, qualitative data was measured accordingly by themes according to the five categories of the PERMA index: positive emotions (P/N), engagement (E), relationships (R), meaning (M), and accomplishment (A). Regarding the PERMA wellbeing index measure of fulfillment and flourishing, jazz musicians noted two out of five elements were the most important: engagement and relationships. “Engagement” is having a ‘flow state’ with one’s instrument or improvisational music practice. The theme of “Relationships” meant the social connections made through playing music, and social identity as a musician - were indicated as being most valuable regarding life fulfillment. These results were slightly different to prior studies of classical musicians (Ascenso et al., 2017), who evenly indicated their value of benefits in all PERMA categories, including positive emotions from playing (P), the meaning or purpose that doing music gives them (M), and the sense of intrinsic internal accomplishment (A), such as from learning a hard piece of music or improving a skill. So the key distinction of fulfillment (wellbeing) for improvising musicians - distinctively from classical musicians - are the key social connections of playing jazz improvisation, and the individual experience of ‘flow state’.

CoNCLUSIONs

Since WWII, the social and cultural perception of artists in the US has remained that arts and public radio should not be government-funded (with roots in cold-war era fear of communism). The Works Progress Administration (WPA) act born from FDR’s New Deal was one of the only federal acts to fund the arts, and has not returned since the 1940’s. The NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) is the sole provider of the tiny 1% of total federal arts funding in the US. State governments provide 12%, non-profits and private donation form 43%, and the remainder is left at mixed-market (ticket sales or popularity - read: large parts of the money funnel goes to industry gatekeepers, PR people, and distributors). One study (Lowell, 2007) showed that 95% of NJ artists were unaware of the New Jersey state arts council, and of the artists who were aware, they generally disliked it due to prior grant rejections or a lack of ‘cool cache’. Artists deal with the public perception of where they obtain their funding from, in addition to the laundry list of issues they face.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY, TECH, NON-PROFIT, AND GOVERNMENT SUPPORT OF Arts IN THE US

It is important to examine the various social and cultural difficulties musicians face within the US. The misnomer of ‘doing what you love’, or ‘playing’ suggests musicians must not be ‘working’, is an uneducated view albeit largely held in the US, reflecting the lack of worth placed on art. Male musician participants more often noted harassment in the form condescension from non-musicians regarding lower and unstable income, while female and non-binary participants indicated more frequent harassment, more often in terms of gender discrimination within the community and by non-musicians alike.

Five ways to improve musicians’ mental health and wellbeing in the US come in the form of social, financial, and mental wellbeing via structural, governmental, corporate, and tech sectors. I will make a few suggestions from key points of the data. 1) Clearly increased arts and music education would help cultural reforms needed in the US to help musicians with the psychological challenges of a career in jazz and improvisational music on a social and structural level within the US. 2) The longstanding decades-old issue of New York venues that do not pay performing musicians (tipjar venues) is an initial issue to tackle for the city’s environment of artists; requiring some structural support to assist musicians financially directly. Amendments to the current federal and state arts institutions’ funding-to-artist pipeline must be made on behalf of jazz musicians in terms of ensuring that money from structural budgets (such as the Shuttered Venue Operators Grants) actually reach performers, not just institutions and employed organizational staff. 3) Decreasing ‘hoop-jumping’ in the forms of applications (grant applications, housing applications, taxes, unemployment applications and other financial support or work qualification processes) would help musicians access the support they need structurally. Participants indicated a barrier of ‘hoop-jumping’ by grants and funding institutions through the vetting process that was exhausting and seldom rewarding (only 1-5% of grants are actually awarded to applicants, suggesting a deep psychological fatigue of ‘funding applications’ and paperwork / application disenfranchisement). Government implications for reform include making income tax filing easier or more widely recognized for freelancers. Despite 95% of the workforce losing their livelihood overnight due to the pandemic, over 1/3rd of musicians (35%) did not apply for unemployment, suggesting a general disenfranchisement and despair over government paperwork of taxes, and a lack of access due to the undersupported gig economy worker unable to provide income paystubs in the accepted forms of W2s and 1099s. 4) Assistance for musicians by union or organizations is due to their overall limited bargaining power - as evidenced by participant frustration with the musicians’ union to increase paid job opportunities city-wide (my survey showed less than 5% of NYC musicians actually have a union job on Broadway or TV/Film music composition, compared to the union’s survey, reporting 40% of union members have union work and an annual income over 40k (most musicians do not find membership useful due to the high annual dues fees and lack of available paid jobs). 5) Finally, accessibility must be improved for jazz musicians of all generations, in particular for elder jazz musicians who are often without the technological and digital literacy needed to apply for assistance and artist funding through the applications that cultural institutions currently disseminate. Due to the history, infrastructural funding issues to reach artists, and nature of limited government funding for the arts, the government, tech, and corporate sectors have an ethical duty to ensure their company products directly benefit and pay musicians. One governmental regulation that could provide the largest benefit for musicians’ overall wellbeing would be for the US Copyright Office (USCO) to revise the 2018 DMCA act to require big tech companies to pay musicians a living streaming wage akin to radio royalties (for example, .01 cent per play versus .0038 cents per play).

References

Gross, S., & Musgrave, G. (2016). Can Music Make You Sick Part 1? A Study Into The Incidence of Musicians' Mental Health.

Gross, S., & Musgrave, G. (2017). Can Music Make You Sick (Part 2)? Qualitative Study and Recommendations.

Gross, S. A., & Musgrave, G. (2020). Can Music Make You Sick?: Measuring the Price of Musical Ambition. University of Westminster Press. Chicago

Iyer, V. (2019). Beneath Improvisation. In The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory.

Liscia, Valentina Di. “95% of US Artists Have Lost Income Due to Pandemic, Survey Says.” Hyperallergic, April 24, 2020.

Music Workers’ Alliance. (2021). Google Docs. “MWA Statement to Gov Cuomo 1:13:21.Pdf.” Accessed May 28, 2021.

Toynbee, J. (2017). The labour that dare not speak its name. Distributed Creativity: Collaboration and Improvisation in Contemporary Music, 2, 37.

Wills, G. I. (2003). Forty lives in the bebop business: Mental health in a group of eminent jazz musicians. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(3), 255-259.